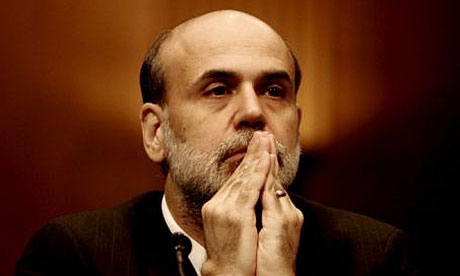

Ben Bernanke, US Federal Reserve

chairman, is hoping that the central banks' concerted action will

prevent a cash squeeze worsening eurozone banks' problems. Photo: Stefan

Zaklin/EPA

Why did six of the world's central banks, including the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, announce new co-ordinated action on Wednesday?

Why did six of the world's central banks, including the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, announce new co-ordinated action on Wednesday?• What are the central banks doing?

They are taking action together to prevent the markets' panic about the future of the eurozone and the health of the banking sector from turning into a full-blown credit crunch, when banks refuse to lend to each other.

• How will they do that?

The Federal Reserve will make it cheaper for other central banks to borrow dollars; they will in turn lend those dollars on more cheaply to their own banks, cutting the interest rate on so-called "dollar swaps" by half a percentage point. In effect, it is an interest rate cut for banks. Although these so-called dollar swaps are available in all the countries involved, they are aimed specifically at tackling a shortage of dollars among the eurozone banks.

All the central banks have also agreed "temporary bilateral liquidity swap arrangements", so that if their domestic banks are running short of any currency, the central banks will be able to provide it at short notice.

• Why do European banks need dollars?

They have been lent large amounts by US investors, including banks and retail money market funds. Many of these investors have been pulling out over the past few months, as the eurozone debt crisis has exacerbated concerns about the solvency of eurozone banks.

That means the European banks need to pay them back, in dollars. They can only get hold of those by attracting dollar-denominated deposits, or by borrowing dollars in the financial markets. That has become more difficult and more expensive for banks during the crisis, amid growing doubts about their solvency.

• Who's involved?

Most of the world's major central banks: the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of Canada and the Swiss National Bank.

• How does this affect British banks?

The Bank of England had a dollar swap arrangement in place during the crisis, which was reinstated in May this year, as the strains in the eurozone began to show.

Since then, no British bank has used it, suggesting that they are not running short of dollars, but the lower price may tempt some to borrow from the Bank, rather than in the open markets. These measures are aimed mainly at the health of the eurozone banks – and the US investors exposed to them.

• Does this solve the problem in the eurozone?

No, it should help to ensure that European banks are not driven to the brink of collapse by a short-term cash squeeze. However, it does nothing to deal with the underlying issue: the heavy debt burden built up by some eurozone countries during the good times, which few analysts now think they will be able to repay.

• What happens next?

Financial markets will be watching the (latest) crucial meeting of eurozone finance ministers next week, as they battle to devise a sustainable solution to the crisis. The European economic and monetary affairs commissioner, Olli Rehn, warned ministers on Wednesday that they have 10 days to save the single currency.

• Is Europe on the brink of recession?

Yes, share prices rocketed on news of the central banks' intervention but the co-ordinated action was a sign that Sir Mervyn King, Ben Bernanke and their counterparts around the world are deeply concerned about the impact of the banking squeeze on the real economy. Already, the Bank of England has warned that there is evidence that eurozone banks are pulling back on loans to businesses and households – and that hits demand. Most economists believe a recession in the eurozone is now all but inevitable. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development said this week that it may already have started.